- Home

- Laurie Steed

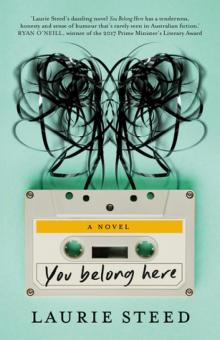

You Belong Here

You Belong Here Read online

Laurie Steed is an author and editor from Western Australia. His fiction has been broadcast on BBC Radio 4 and published in Best Australian Stories, Award Winning Australian Writing, Review of Australian Fiction, The Age, Meanjin, Westerly, Island, Kill Your Darlings, The Sleepers Almanac, and elsewhere. He is the recipient of fellowships from the University of Iowa, the Baltic Writing Residency, the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation, the Katharine Susannah Prichard Foundation, and the Fellowship of Australian Writers (WA).

He won the Patricia Hackett Prize for Fiction in 2012, and was selected as the first Australian Fellow in the history of the Sozopol Fiction Seminars in 2014. He lives in Perth with his wife and two young sons.

Published by Margaret River Press in 2018

Copyright © Laurie Steed 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the Australian Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior permission in writing from the publisher of this book.

Margaret River Press

Web: www.margaretriverpress.com

email: [email protected]

Cover design: Debra Billson

Editor: Kate O’Donnell

Typesetting: Midland Typesetters, Australia

Set in 11.5/16 pt Adobe Garamond Pro

Printed by McPherson’s Printing

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN: 978-0-6482039-0-2

Contents

1972–1984

Departure

The Middle of Somewhere

The Family Mixtape

Before a Fall

Wallpaper

1985–1995

Just Hits ’85

Eternians

Girls Don’t Cry

The First Test

The Knife

1996–1999

Half-Life

One and Only

Three letters in relation to the unforeseen and unfortunate demise of the precarious but ever-lovable mind of our son and brother, Jay Slater

Skin I’m In

Once

Jay Begins

I Got You

2000–2002

Give or Take

The Gap

Twenty-eight steps: Or, the thoughts of Jay Slater on the untimely and unfortunate implosion of the Slater family (revisited), 28 March 2001

What It Is

Arrival

2015

The World According to Val

Acknowledgements

1972-1984

Departure

Jen sat sketching flowers on the back steps, the chalk worn down to a nub. She wiped away the flowers and began again, this time with slower strokes, her fingers inching across the concrete. She chalked David Cassidy, hair flowing down to his shoulders. Smudged him out with the tip of her finger, wondered when, or if, she would ever do something right.

‘Sophie’s here!’ called her mother from the kitchen.

Jen wiped her hands on her dress. Took a bucket, filled it. Splashed the water on the concrete and washed a line of ants away in a milky stream. Tipped the bucket on its head and went inside.

‘Jen!’ her mother called again.

‘Coming!’ She headed through the back room, past the laundry, and into the kitchen.

There was little to shout about in Brunswick West. Most evenings stretched out to nothing but the neighbour’s EB, left idling in the driveway.

Word was that her mum and Mr EB had bumped uglies a year or so back. His wife left a box on their front doorstep not too long after. A frayed toothbrush, an empty tub of Brylcreem, and a bar of Palmolive worn down to a wafer, a pubic hair still stuck to its surface.

Not much to say after that. The wife left. She’d come back on weekends, watch the house from her car with a box of chips and gravy. Jen waved at her a couple of times and the wife waved back, but the arc was all wrong— a left–right tilt—and to Jen it resembled the swipe of a windscreen wiper.

She pushed open the kitchen door, left a chalky print. Sophie was propped against lemon-yellow cupboards in a black tee and low-rise flares, reading New Idea.

‘Foxy,’ said Jen, trying her sexy voice.

‘I didn’t know you cared,’ said Sophie. ‘It’s always the quiet ones.’

‘Give me a sec. I need to get changed.’

‘Take your time. Your mum’s making dinner. Speaking of which, are we eating here?’

‘Do we have to?’

‘There won’t be drinks at this party, will there?’ said Jen’s mother.

Jen and Sophie exchanged looks.

‘Maybe punch,’ said Jen.

‘Non-alcoholic?’

‘I think so. How will we know?’

‘I’ll know,’ said her mother. ‘And you’re only sixteen, so no silly stuff, all right?’

Jen’s mother offered to drive them. They said they needed to stop by Sophie’s, but instead crept into the back end of Royal Park.

In truth, Jen would have walked to St Kilda to save a drive with her mum. It was not that her mum had lost the plot, but rather things had been revealed over time. Jen’s mother had taken to forgery: black strikes through her daughter’s dress sizes, replaced with the number six. Constant questions about whether Jen only stayed around because she had to; if, given the choice, she would leave, as her father had.

Requests for her daughter to reach out to her father, to tell him it was all so foolish, and maybe he could come back, and they’d give it another go, try their best to again be a family.

Other smaller things: an obsessive leaning towards canned goods; late-night sobs, heard through the walls, as if they were the wind, or the creaking of the floorboards.

In isolation these things were not particularly strange, but together they formed a gallery of tilted paintings. It was all Jen could do not to measure them with a spirit level, adjust them one by one in the hope of finding balance.

Perhaps her mum suffered from a serious malady or affliction. Jen had browsed the local library on more than one occasion, reading mostly volume II of The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, finding little that defined or delineated her mother.

She wondered if it mattered what was wrong, or whether it was just as helpful to say She’s not right, or She’s sick in the head. She wondered if she’d ever find a fit for anyone in her immediate family in a book so black and white.

She dispelled the thought as they walked into Royal Park. Saw it in a bubble, let it float up, and popped it as it reached the clouds above. A wave of relief and the guilt that always followed; a shake of her head, an overwhelming desire for things to be blurred, or softened.

They found a bench, necked a couple of beers from Sophie’s bag, midges hovering above like floating, swirling quotation marks.

‘This is gross,’ said Jen. ‘How do guys drink this?’

‘They’re idiots,’ said Sophie.

‘I saw one once,’ said Jen, lifting her thumb and finger, measuring out an inch.

‘What?’ said Sophie, laughing. ‘A guy?’

‘No,’ Jen whispered. ‘A thing .’

Sophie squinted.

‘You know, a penis,’ Jen continued.

‘Did you touch it?’

‘It was in Cleo.’

Sophie raised her hand to her face and left it there, as though shielding herself from the image. ‘Why are you telling me this?’

‘It’s the drink,’ said Jen, laughing. ‘I can’t censor myself.’

She ha

d drunk before, a glass of beer, her father’s gift for her fourteenth birthday. She had pretended to like it. She’d loved the way her father had smiled back that day, been happy to have found the slightest connection.

It hadn’t lasted long, that serenity. After he left, they had cleaned out the cupboards, discarding shoes, singlets, and old magazines.

‘He wasn’t happy,’ her mother had said to her, more than once, as if, by repetition, she might dispel the grief. Her mother had a way of doing this. Of saying nothing, creating portraits without ever completing the picture.

Sophie took a hipflask from her back pocket. Had a swig, winced, and then took another mouthful.

‘What’s that?’ said Jen.

‘Bourbon,’ said Sophie. ‘It’s like whisky. You want a sip?’

Jen nodded, drank a mouthful, and coughed.

‘You,’ said Sophie, ‘are a bloody fool.’

‘And I love you,’ said Jen, struggling to focus as she pointed, her finger moving left then right in search of her friend. ‘Actually, I love Steven. You know Steven, right?’

‘You talk about him every time we catch up,’ said Sophie.

‘He’s very cute,’ said Jen. ‘A prince of a man.’

‘All right, Cinderella,’ said Sophie. She took a swig. ‘What you gonna do, root the guy?’

‘You’re so crass sometimes,’ said Jen. ‘Me and Steven, we have an understanding.’

‘You’ve never spoken.’

‘But we will.’

Jen felt as though the earth was slightly on a lean, knocking her off balance. Adored the way that Sophie spoke, half queen and half tradesman.

‘I like this,’ she said. ‘Makes things fuzzy.’

The bottle shop was on the corner of Brunswick and Sydney roads, out the back of the pub. Jen had deliberately worn her most mature outfit—a blue rayon wrap—and had flicked her hair out, hoping it made her look older.

‘You ready?’ said Sophie.

‘Certainly.’ Jen’s new accent was absurdly posh. She giggled.

‘Wait at the door. I’ll sort this.’

Sophie entered the shop, a hovel of a bottle-o, mostly beer and a few spirits. Jen followed and immediately wished she hadn’t. The space was dark, tiny. It echoed every step she took, each reverberation deafening in the silent room. She picked up a bottle of wine, squinted at the label.

‘What did I say?’ said Sophie.

‘I don’t remember,’ said Jen.

‘Wait outside,’ Sophie whispered.

‘Right,’ said Jen, also whispering. ‘I’ll see you soon.’

She turned and as she did knocked over a display of wine bottles. One tilted off the box and onto the floor, rolling down the linoleum.

‘Sorry,’ said Sophie, as a man with white, wispy hair and a belly bump the size of a baby emerged from the back.

‘You girls aren’t trying to buy grog, are you?’ said the man.

‘Yes,’ said Jen.

‘She means no,’ said Sophie. ‘Come on.’

Outside, a red Datsun 180b pulled in with a crunch. The men inside the car whistled at the girls as they passed, and the girls stared back, laughing.

Jen tried, but struggled, to balance along a faded white line, as though walking a tightrope. Performed en pointe, dancing on tippy-toes in her shoes. She started to wobble, landed back on her heels, and finished the movement with an outward flourish of her hands.

‘Are you drunk?’ said Sophie.

‘You know,’ said Jen, tilting her hand back and forth, ‘I really don’t think so.’

A boy, lean with short kempt hair pushed behind his ears, was standing against the wall. He arched up when he saw them.

‘God, it’s him,’ said Jen. ‘Quick, hide.’

‘Oh brother.’ Sophie pulled at her friend’s arm.

‘Hi,’ said the boy. ‘You’re Jen, right? We went to school together.’

‘We did?’ Jen smiled.

‘I was in the year above,’ he said, ‘but now I’m doing my diploma in aviation. I’m Steven.’

‘I know,’ said Jen. She bit her bottom lip. ‘We’re headed to Tina’s party . . . See you later on?’

‘Sure.’ He tapped his foot. Looked left, right, and then straight on, locking eyes with Jen. She couldn’t help but feel it was a move he had practised in the mirror.

She twisted the ring on her third finger until it rested near the knuckle, and then gently slid it back into place.

‘See you sooner, or later,’ she said. She’d meant to sound coy, but it came across as vague.

He laughed, gave a mock salute, and watched as they left.

Jen carefully squeezed through the gap between two parked cars, brushing a side mirror. She pushed it with her hip and it sprung forwards with a turnstile click.

The Middle of Somewhere

By 1975, Jen and Steven were married. Nothing fancy, just family and friends at the local church. Jen’s mother had even splurged on a peppermint-green Rolls Royce, although the exhaust rattled and the engine made the seats shake.

Steven had completed his Diploma of Aviation in 1972, and by the time of their marriage in December 1974 he’d been at Tullamarine for two years. Jen found a job in Belgrave the year after, receptionist to an air-conditioning company, and was about to quit on account of the long drive when Steven had received a call from Perth.

A career opportunity.

Steven and Jen flew over, business class, in a 727. Two nights at the Sheraton, some swanky new hotel in the CBD, with minibar, drinks, and breakfast included.

No mention of shifts, or the adaptation to new streets, and smaller malls; a city not yet visited, let alone inhabited by the Slater family. They’d arrived in Western Australia the way most did, unsure of whether they were at an airport or an aircraft hangar. They had taken one of the three cabs in the rank, the driver only kicking into action once they’d visibly lifted their suitcases towards the boot. They vowed to see something of the city, preferably in the shade, given it was only mid-December but thirty-two degrees and headed for a late afternoon peak of thirty-four.

With interview completed, and a shower and change of clothes, they had found Kings Park, a sprawling mass of green that cloaked a cliff to the west of Perth’s CBD. Steven dressed, as always, in pressed navy trousers and a sky-blue business shirt; Jen in a green and white summer dress, cape-collared, that bumped at the breasts and bulged at the belly. She wasn’t very comfortable but was damned if she was going to travel to a place like Perth and dress as though she was in Melbourne, with its morning chill and windswept laneways, refusing sun, as though to let it in would be distinctly un-Victorian.

Lanes of cars coasted north and south on the freeway. What appeared to Jen as a Tolkien-like valley in old photographs had in time been overtaken by lights, roads, and office blocks. The buildings like Lego—tubby, flattened thumbs held up on the horizon. The river spilling out, centre stage, ripples emerging every now and then from the shadows, a blanket of black stretching the gap between north and south.

Steven had brought along two pies, a bottle of white, two plastic glasses, and a corkscrew. No napkins or cutlery. No plates, either. A man’s picnic, she thought, as he emptied the bag. She appreciated the thought as she’d appreciated his other little quirks: petals on the bed with each anniversary; the care with which he entered her when making love, as though prolonging every second.

‘We should make out,’ said Steven.

‘You’d love that, wouldn’t you?’ said Jen.

He nodded, smiling. ‘You would too. You think I don’t know why you brought me here?’

For a second she felt drunk on love. Happy, hopeful they were doing this together. She reached for his hand and he squeezed hers twice, but then his grip loosened, and it seemed he was thinking about something else: a möbius strip of past and present, with neither gaining traction.

A mosquito landed on her leg and she shooed it away, her stockings too tight, her jacket zip st

retched near the belly. Moon Jen , she thought, swallowed a beachball.

She took a bite of her pie. Swallowed twice to get it down. Remembered that at primary school, they had found a piece of pigskin in a steak and mushroom pie; a pink, rubbery flap, with fine golden hairs on one side, baby smooth on the other. She felt sick. Put down the bag, pushed it to Steven, who took a bite, and then another, and soon enough he was on to his second.

Every so often a light, warm breeze rustled through. To the east a full, heavy moon touched the hills.

Jen took her husband’s arm, draped it over her shoulder, kissed the back of his hand. A midge landed nearby. Steven kicked, his foot flailing. The midge flew up for a moment and then landed again. He kicked it again, and it flew away.

‘You like Kings Park?’ said Steven. ‘Could be our new hangout?’

‘Let’s see if you get the job first, hey?’ said Jen.

‘We’re out west. You afraid?’

‘Of what?’

‘Drop bears. They prey on virgins.’

‘I should be all right then,’ said Jen.

Should be, would be, although none of that was thanks to Steven. She had come to expect his state of chaos: the need to be on call, the shift that could come at any time with news or opportunity. He had only added to the maelstrom; had researched blue-chip western suburbs in Perth, drawn up comparisons on graph paper. Chose Mount Lawley in the end because it was closer to the city, and near enough to the airport for the commute to be manageable.

‘It’s weird,’ said Jen.

‘What?’

‘Perth. It’s like an island. Australia’s shed, down the back of the garden.’

‘You going to be okay?’ he said. ‘To up and move?’

‘We’ve come for the interview. For now, that’s enough.’

‘What if I get the job?’

I’ll be happy. I’ll be scared. Glad to be leaving Mum. Sad to be leaving Melbourne. I’ll need you. You’ll need to keep close, say it’s going to be okay.

‘I don’t know,’ she said, and breathed out, a gentle pulse in her lips at the sudden release of air. She exhaled again to relive the sensation, her mouth only slightly open.

You Belong Here

You Belong Here