- Home

- Laurie Steed

You Belong Here Page 2

You Belong Here Read online

Page 2

An opportunity, thought Jen. A place unburdened by emotional baggage. A town playing grown-ups, with a river that split the centre like a giant sinkhole, only pretty, that slick of a sinkhole, so long as you wanted to fish its depths, sail the surface, or jog its perimeter.

Not a bad get, all told, but miles away, and isolated. The place was hotter too, bigger in some respects and yet small at the same time. More a town than a capital city, and rough at that. They’d had the misfortune of walking down the wrong side of Barrack and things quickly went downhill. Hoots and hollers from Ziggy’s, Friday afternoon skimpies, and a woman at the No. 60 bus stop sipping slowly—and, it seemed, a bit painfully—on something purple in an old lemonade bottle.

‘This is home,’ said Steven.

‘Maybe,’ said Jen.

‘What’s going to sell it? We’ll get a bigger house, and it’s much quieter. Never have to trek Sydney Road again. Imagine that.’

And she did, but she wasn’t that excited.

‘I’ll work part-time, if we need it,’ Jen said.

He motioned to her belly, a slight but deliberate glance.

‘I can still work, Steven.’ Jen said.

‘We’ll see,’ he said in a soothing voice, although she felt patronised. As though, with every ‘we’ he meant ‘he,’ and by ‘see’ he meant to never again discuss her working life.

He reached for her belly bump. ‘I love you.’

‘I know.’

He moved closer. Rested his palm on her stomach. Drew a heart with his index finger. She gently caressed his hand, and soon enough she could barely recall the ways in which she felt hemmed in, or restricted.

‘How are you feeling?’ she said.

‘About Perth?’

‘About this,’ she said, patting her belly.

‘Great,’ said Steven, smoothing the rug. ‘You?’

‘Great,’ she echoed. She waited for a follow-up question, but he let it go.

She was not sure if he was tired, stressed, or maybe both. Whether, in those sighs and silences she was seeing a sunken intensity that would flare up when things got too much or the tasks too many for him.

She had planned to tell him in the car that she was terrified of the move, and maybe it was all too soon. That it wouldn’t have to be forever, but right now they were having a baby, which was more than enough to worry about. She baulked, of course. How did you tell your husband such things? When was it anxiety and when were you simply sharing your thoughts and fears with the man you love in the hope that he might hear them?

‘Can we go for a walk?’ said Jen.

‘Sure.’ He picked her up from the rug, strained for a second. They shoved their things into the bag and walked on, the city shifting into view. Down to the war memorial, feeling naked in the throng of people, tourists with cameras, framing and reframing the night-time cityscape. They found the last spot on the rail.

Jen felt shadowed by the giant monument, clouds drifting down as if preparing for a storm. ‘We’re having a baby.’

Steven rested his hand on her belly, traced semicircular motions with the tips of his fingers. ‘How are you holding up?’

‘I’m a bit scared.’

‘I know,’ said Steven. ‘But we’ll be okay.’

They kept walking. Down the edge of the park. The trees thinning. The river, spreading out, almost a lake, as houses and units shone like tea lights.

A gazebo appeared at the point where the path dipped down. Her feet already ached, the extra weight tightening her lower back. She wanted to be close, thinking maybe it would crack him open, spilling out thoughts and fears.

‘Take a break?’

‘Oh,’ said Steven. ‘Absolutely.’ He laid the blanket down, helped her to the ground. He remained standing and watched, as though assessing danger.

She pulled at his trouser leg. ‘What are you looking at?’

‘Cumulus clouds,’ said Steven. ‘Loose formation.’

‘I have a loose formation that needs some attention,’ said Jen. She zipped open her jacket and plumped up her cleavage.

Steven smiled and went down on his knees. He was about to open Jen’s blouse when she clasped his fingers.

‘Remember our first date?’ said Jen.

‘No,’ said Steven.

‘You do,’ she said, smiling.

‘I do,’ he said. ‘You think I’d forget that?’

She had worn a green tube top and jeans. A scarf with sparkles in the fabric, hoping maybe she could shimmer, diamond shine.

‘It was nice,’ said Steven. ‘Almost too nice.’

‘What do you mean?’ said Jen.

‘I wasn’t sure it could last. That things could stay that good.’

‘Lucky you stuck it out,’ said Jen. She kissed her husband, her nose knocking his glasses off kilter.

So lucky, she thought, as though the very idea would implode if spoken, a mantra she’d embrace when nights were long, or when fear took over.

He slipped her dress off her shoulders, nuzzled her breastbone. She took his shirt off button by button, kissed his centre line from neck to navel, her nose tickling his chest on the way.

‘I’m not sure I have this sex thing right,’ he said. ‘Can we give it another try?’

She nodded. Undid his belt and zipper, slipped his jeans off, leg by leg. She grinned, crawled up, placed her palms upon his shoulders.

She bent over, hair draped over his rib cage, dipping down to kiss his belly, higher, higher, until reaching his lips. Steven pulled at her dress. A shoulder came down, exposing her breast. He went to grab it, but she slapped his hand. She tugged at his underpants, slid them down to his ankles.

She started slow, rocking back and forth, occasionally shifting her weight left then right. Spread her hands across his chest, tightening her grip. Thrust up and down, locked upon a single word. Together. Together . Together . Together .

The bub kicked in her belly and she wondered if, despite her joy, she had made an unconscionably selfish choice: rocking, fucking, longing, all at once. Threw away her guilt, cursed herself for thinking such things. Put the thought in a bubble, popped it with a thrust, and another, thoughts coming, gone, body flooded, tingling in a moment of release, and still her mother’s voice, persistent, loud. You’re so selfish, Jen. I don’t like selfish people.

But families are selfish. They’re mums, dads, kids. Together.

She came hard. Shuddered twice and then stretched, as though eking out the last ounce of pleasure. Lifted her leg, rolled onto the rug. Lay beside him, twirling his hair in her fingers. They turned to each other and, for a moment, were silent.

‘That was nice,’ said Jen.

‘You sound surprised,’ said Steven.

‘No, it’s just, well, work, and with Alex on the way. We’ve let it slip a bit.’

‘Who’s Alex?’ said Steven.

‘I thought we could call him that,’ she said. ‘You don’t like it?’

‘I love it. What’s his middle name?’

‘There’s plenty of time to work that out,’ said Jen, feeling foolish, hopeful, frightened. ‘Cuddle me.’

He cuddled her, and she liked the way he gave in to the cuddle, hoping one day she could be like that, thoughts thrown out to the wind, eyes closed, feeling love, or something like it.

The Family Mixtape

For Jen, 1980 meant wake-ups at six with if not hope then at least a sense of contentment. Her nights no longer burdened with feeds, or early morning settles in the glow of Jay’s night-light.

She woke the kids with a single knock, except for Jay, who got the open-door-lift-up-and-carry-out-to-the-kitchen-table treatment, not because he needed it—at two years old, he now bounded around the house—but because she loved the nearness of him: the soft, almost fabric-like scent that lingered on her little man.

She had promised Alex a day, just her and him, as he’d taken to pissing in the corner of the boys’ room. Not fair or okay, but a thing that was ha

ppening. They’d done okay in terms of their family home, a two-storey, three- bedroom house in Mount Lawley with a fair backyard and a mortgage to match. Still, that didn’t mean Alex had fully processed the latest addition to the family, or the smaller bed that now sat parallel to his.

Once all of the kids were in the car, she dropped off Jay and Emily at Sophie’s, along with two banana sandwiches, a carton of choc milk, and a Wombles video. Jen was grateful to have her friend in the same city again. Sophie had found only judgement after coming out to her family, and their explicit disapproval had begun to seep into Melbourne’s streets, extending to neighbours and family friends. Sophie had rung Jen, asked what it was like to live in the most isolated capital city. It’s not bad, she’d replied, and it’s not like there’s no-one here, just less people on the whole. Perth had only one gay bar that prided itself on a culture of inclusion, all the while stationed in a city where connection was sporadic, friendships spread too thin across an ever-expanding suburban sprawl.

Jen parked the car. Juggled her handbag in her left hand and a plastic lunchbox in her right, slamming the boot shut with a thrust of her elbow. She and Alex walked between the wooden bollards that were stained a darker rusted brown from years of bore water sprinklered onto the grass.

Alex wore a yellow sunhat. She pulled it over his eyes, pushed him slightly with her hip. Alex laughed, briefly, before his gaze drifted back to the ground. He kicked at the grass repeatedly, his shoe bending at the toe.

‘What are you doing?’ said Jen.

‘Making fire,’ said Alex.

‘Don’t be silly.’ She looped a finger through his belt, tugged him back to the path. ‘You can’t make fire. You’re inflammable.’

‘What’s inflammable?’

‘It means nothing can hurt you,’ said Jen. ‘At least, I think that’s what it means.’

She stared at the sky. Thought maybe she should do this more often, but with friends. She couldn’t stand the thought of being so alone in such an open space.

‘Race you,’ said Jen, and together they bolted. She let him win. Alex lifted his arms in celebration and then stumbled, an almost-fall.

Hamer Park had become Jen’s second home. Two wide, near-identical ovals, bordered to their left by a rising crest that led to quiet streets and family homes. To their right, the speed bump boundary of Inglewood Oval, hidden by a fence of eucalypts.

‘Jack and Jill!’ said Alex, running up the slope.

‘Jack and Jill went up the hill to fetch a pail of water,’ said Jen.

Alex stopped.

‘Jack fell down,’ she said, watching with glee as he ran down, arms stretched out. ‘And broke his crown,’ as he fell to the ground, ‘and Jill came tumbling after.’

She fell on top, tickled his ribs, so that he squirmed and giggled, both at once.

‘When will Dad be home?’ said Alex.

‘He has to work, chook,’ said Jen. ‘But he loves you very much.’

‘Can we have ice-cream?’

‘You’re allergic to ice-cream.’ She stood, extending a hand to Alex. Lifted him up and dusted him off. ‘If you’re hungry, there’s a sandwich.’ She fished into her bag, pulled out a square Tupperware container.

‘Ugh,’ he said, but took the box and prised open the lid. He stuffed half a sandwich into his mouth, pulling off the crusts and giving them back to his mother. He chewed, as though working through a marshmallow.

‘Yuck,’ he said, and ran down the path singing ‘Jack and Jill’ extra fast. Jen stuffed the crusts in the lunchbox, closed the lid, and jogged after him.

A man stood on the path, holding his daughter’s hand. Hard to believe he was a dad: eyes so bright and cleanly shaven.

‘Mum’s day out?’ said the man, drawing level.

‘I guess that would make you dad,’ she said, smiling.

‘You been to the school? My girl Natalie starts next year. Not this one,’ he said, patting his daughter’s head. ‘She’s too little.’

‘Alex starts next year too. He’s at kindy.’

‘Perhaps they’ll be friends.’

‘I hope so,’ said Jen, and walked on, feeling lonely as soon as they parted ways.

‘Mum!’ yelled Alex. ‘Mum!’

Jen sighed, took a breath, and ran to catch up.

The weather shifted, a scattering of clouds that cast shadows across the park. It grew colder, as though the sky itself was lost in sadness or regret.

Alex ran up and down the crest of Inglewood Oval, making plane noises as he crossed Jen’s path. He slowed and crouched down.

‘Alex,’ she said. ‘Don’t touch that.’

He’d seen a used condom. ‘Why?’

‘Just don’t,’ she said, and he moved on.

Another thing to worry about. She had warned him about strangers, said to always wait for the green man when crossing. So much to fear outside the front door, with cars going sixty, branches breaking, and stormwater drains the right size for a small child.

She ran to Alex, took his hand, but he pulled it away. For a second he looked like his father: face in a scowl, craving distance.

‘Baby, come here.’

Alex put his hands in his pockets and shuffled towards her, looking down the whole way.

‘You always yell at me,’ said Alex.

‘No, I don’t,’ said Jen.

‘Am I bad? Is that why Dad’s at work?’

She softened. ‘It’s hard, hey?’

He pouted, kicked at the grass. ‘You’re a fibber. You said he’d get a day off.’

‘Baby.’

‘You said,’ said Alex. ‘You promised——’

‘Let’s go home then, hey?’ said Jen. ‘Would you like that?’

Though she knew he was just a kid, there were times she sensed a similar single-mindedness that often surfaced in Steven. As though his father had snuck in late, said, Son, there’s not much I can teach you ’cept to put your foot down hard, as though it is your right, your only way of being.

Crazy, she thought, although the word felt more like a plug than the flowthrough of thought.

She leaned down and swept Alex up, her arms wrapping around his waist. He struggled, hit out at her hips, legs, and stomach. She hurriedly carried him back across the park. As they neared the car, he turned and her grip slid down. As she tried to adjust and hold on to his legs, he slipped from her grasp and fell headfirst—a dull thud as he hit the ground. He tumbled, slumped onto his back, and turned quickly to his side, his cries echoing out across the empty oval.

‘Alex!’

She gasped, and dropped to his side.

*

They stopped at Sophie’s. Jen rushed in, while Alex stayed in the backseat, sulking.

‘You okay?’ said Sophie.

‘It’s Alex, he’s a bit shaken up,’ said Jen. ‘I wanted to ask if you could take Jay and Em for the night.’

‘Of course. As long as they’re okay with that.’

Emily nodded, barely looking up from her copy of Mister Magnolia.

Jen paused, taking in her daughter. At three years old, already so smart but so closed off. Jen wondered if she had already made a misstep, and how she’d missed making it. She kissed her daughter’s forehead and Emily lifted her arm, slung it around her mother’s neck, let her stay for a bit, as if to give her what she needed.

Jay was at the kitchen table eating Coco Pops with a fork, a few had spilled onto the tabletop. She asked if he wanted to stay with Auntie Sophie, like day care.

‘Okay,’ he said, milk dribbling down his chin. He dropped his fork and reached out for a hug. Jen lifted him up, pulling him close.

‘I love you, baby Jay,’ said Jen.

‘Funny,’ said Jay, smushing his face into her cheek.

She drove Alex home. Took her time. She hadn’t wanted to be back so soon, not to a mostly empty house, with him and no-one else.

They got in the house, microwaved macaroni and cheese from the freezer, and w

atched The Muppet Movie.Sat in silence, although he cuddled up to her early on in the film.

‘You okay?’ said Jen.

‘Sorry,’ said Alex.

‘What are you sorry for?’ He didn’t answer and she wanted to press him, but she was sorry too.

Jen glanced over at her son at the midpoint of the film, but he’d already fallen asleep. She carried him to bed, his legs draped over her arms, sneakers knocking against each other.

Jen lifted the covers and gently laid her son on the bed. She kissed his forehead and stroked his hair. Left the door open a smidgen to check on him later.

Crisis averted. Her little man safe, and she’d done all right in the end.

Steven got home late, as he often did. He lay on the bed on his back, stared at the ceiling.

‘Where are the kids?’

‘Alex is sleeping, Emily and Jay are at Soph’s,’ said Jen. ‘You all right?’

‘Rough day,’ he said. ‘You?’

She no longer noticed the days, just feelings, raw emotions, as they washed over. Mother moments, one after the other, sometimes suffocating, sometimes invigorating, and sometimes both.

‘We’re lucky,’ she said.

‘I’m sorry?’ said Steven.

‘You seen our kids? I mean you get pregnant, no clue, and then they’re there, looking up at you with all this hope. Even on a bad day, when you screw up tying their shoelaces because you’re that much of a mess, you’re lucky still. For that. For new memories.’

‘And why,’ said Steven, ‘would you need to get rid of the old ones?’

But he couldn’t know, not like her, and even as he asked, she had already distinguished past from present and was happy to do so. She held her husband, kissed his forehead, held her thoughts down deep, sharp as they so often were, for there was more to say and things to fix, but not now, with them tired, warm, and safe; the doors locked shut, their kids asleep, and the opportunity to go again; to be kinder, gentler, and more patient, hoping that, with each day, you would get another chance.

Before a Fall

Steven sat in the Airport Control Centre, a dimly lit space filled with files, printers, a series of precision approach radar systems, and three uniformed officers, who’d been waiting to speak with him. The radar scopes showed two tracks: azimuth, a plane’s position as relative to the horizontal approach path; and elevation, the vertical position, as relative to the glide path.

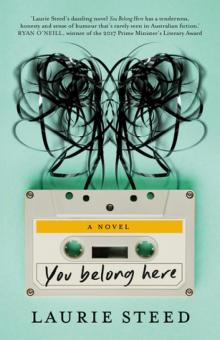

You Belong Here

You Belong Here