- Home

- Laurie Steed

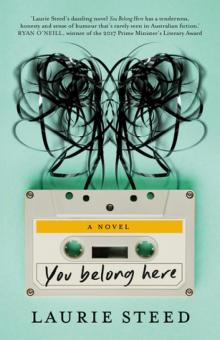

You Belong Here Page 9

You Belong Here Read online

Page 9

The doctor said, ‘Well, that depends on what’s he’s done, and how he’s feeling in this situation.’

Milkshakes at Macca’s afterwards, although they weren’t as great as Emily had remembered them. She brought up Nicky, and Jay shot her a look.

‘It’s not about her,’ he said. ‘It’s about our family.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I can’t fix this,’ said Jay, ‘unless I start again, and me and Nicky, together. It’s very important. I don’t change the pattern, we’re fucked.’

‘That’s a lot of pressure to take on,’ said Emily.

‘Do you see anyone else ready to step up?’ said Jay.

He took the prescription from his sister, gave her a look, and then crumpled, head in hands. He cried quiet sobs, wouldn’t stop, and so they drove around for a bit, took in Matilda Bay, watched the ripples from their spot in the car park, sun-cast path bled orange on the river, till the clouds came back, winds kicked in, and it was time to go home.

Emily called Alex on a Thursday, with Jay holed up watching Dr. Katz back-to-back, with a bowl of popcorn, overfilled, and the lights turned off.

‘Princess,’ said Alex, a little too jovial.

‘Shut up,’ said Emily. ‘We need to talk. Jay’s not doing so good.’

‘And what do you want me to do about it?’

Grow up. Wake up. Help me out.

‘Be a big brother. Take him somewhere, get a beer or something.’

‘He’s all right,’ said Alex. ‘We spoke last week.’

‘Did he mention Nicky?’

‘He’s better off without her,’ said Alex.

Christ. Like talking to a two-by-four.

‘Something happened. With them,’ she told him.

‘Mm-hmm.’

‘Something big.’

‘We all have our problems, Emily.’

A pause. ‘Can you come over?’

He breathed out, audibly. ‘I can’t. Get Dad to do it.’

‘Ha-ha.’

‘I’m serious. Whole place falls apart and where the hell is he?’

‘Can we not do this?’

‘I’m angry,’ said Alex. ‘Perfectly natural emotion. Jay could try it too, maybe stop his vision quest long enough to see he’s chasing a nervous breakdown.’

‘Their break-up was years ago,’ said Emily. ‘How about you both just leave it and get on with your lives?’

‘We could,’ said Alex. ‘It’s just we’re not robots, you know? I’d like to be more like you, really . . . except I’m not sure that you’re over it either. I’ll call him, get together. I have to go, but we’ll talk, yeah?’

She went to say ‘bye,’ but he had already hung up the phone.

Emily had a love-hate relationship with Mount Lawley. She’d met Dom there, jugs at the Scotsman, and soon enough, they had started going out. Or at least, she thought they were going out. Only he never wanted to go out, at least not him and her, and so the streets seemed empty, notably Dom-less, as though he’d been there, lived there, but only for the night, and was now just an added room in an underfurnished duplex.

On one of the many Saturdays when Dom worked, and Jay was coding for a uni assignment, she went shopping with her mother. Clouds crowded the sky, a rarity in December. Looked for a park behind Fresh Provisions, also a rarity, but they found one in the end, closer to the back, and bought sushi for Sophie. They weighed up some videos at Planet, damn near bought the whole shop.

Emily had wanted to get out. Jay had been distant, searching for a break in breakfast conversation, pushing away his toast after only a couple of bites. Before they left, Emily had pushed open his bedroom door, found him staring out into the backyard.

‘You okay?’

‘I’m studying half-life,’ said Jay. ‘Not for uni. It’s just interesting.’

Which was weird but not out of the ball park. ‘You mean radiation half-life?’

‘It’s not only radiation. There’s biological half-life too. You can apply it to anything in a state of decay.’

‘And it’s applicable how?’ she said.

‘It’s not a security code. I’m trying to solve the puzzle.’

‘Um——’

‘Our family,’ said Jay. ‘The ways in which we’re guided by trauma.’

‘All well and good, but can you ask it about paying bills, and not stealing the treats from the cupboard?’

‘Ha-ha,’ said Jay.

‘How are you going so far?’ said Emily.

‘Some pieces are missing.’

‘What’s this really about, brother?’

‘Half-life,’ he said. ‘The ways in which we heal, or don’t.’

Which was pretty much why mother and daughter retreated to the shops. They went to the Dôme café, two large-cup cappuccinos and a spinach muffin with rocks of baked fetta, semi-submerged. Her mum caught a piece of spinach between her teeth, and Emily enjoyed the flaw it provided in her otherwise immaculate appearance.

‘You all right?’ said Jen.

Was she all right? Could you even be ‘all right?’

‘I’m worried about Jay.’ Jen raised an eyebrow. ‘He’s not a kid, love.’

‘He’s seventeen,’ said Emily, stirring her coffee.

‘I had Alex when I was twenty-one,’ said Jen.

And we all know how that turned out, thought Emily.

Between the clattering of coffee cups and the clinking of cutlery, they ate slices of danish, took sips of milky coffee, while outside a crisscross of cars, vans, and utes took the corner of Beaufort and Walcott.

‘Do you know, I haven’t had sex in five years?’ said Jen.

‘Mum!’

‘Well, I haven’t. I’d kill for a bonk.’

‘Can we talk about something else?’

‘You struggling with your desperate, single Mum? We can’t all be Suze DeMarchi, you know.’

‘Do you even know who that is?’ said Emily.

‘Not really.’

Emily laughed. ‘She’s a singer.’

‘I knew that.’

‘Thanks for trying.’

‘Too young to know, too old to listen,’ said Jen, winking.

Emily flicked through the day’s paper, tabloid talk on break-ins and speed cameras, with a dash of the political thrown in.

‘Mal Colston says he didn’t rort a thing,’ said Emily.

‘He could do with a rort,’ said Jen, and they laughed.

‘Hey, Mum.’

‘Hmm?’

‘I’m worried about Jay.’

‘Me too,’ said Jen. ‘But he’d tell us, right? I mean, if he wasn’t coping? I know he wallows sometimes. I figured that was what we’re dealing with.’

Emily wanted to believe that Jay had the capacity to call for help if needed, but at the same time, it wasn’t as though there was precedent. For the most part, Jay had propped them up; only now it seemed he’d found a crack, worried that things no longer worked out as a matter of course. Thinking that until now, he’d been lucky, blessed, oblivious to the breaking of glass, or the wonder of misconception.

Emily slept for most of the night. Got up at around two-thirty to go to the toilet. Jay’s light was on. She knocked twice, waited.

‘What?’ said a voice, annoyed.

‘Can I come in?’

‘Ugh. All right.’

She had expected to find something tangible: a bong or bottle, an open chat, or a video game. Instead she found only Jay, his hair messed up, and thinner than healthy in a white tank top and track pants.

His room was strewn with posters stuck on the walls. As always, the same Propellerheads poster: two shadows in the dark, walking on, backs turned from an explosion. His choose-your-own-adventure books pulled from the shelf and scattered around the room.

She pointed at the books to the side of his bed. ‘You giving them away?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Turn to page twenty-five to find out,’ said

Emily, attempting a joke, but he didn’t seem to hear, and, instead, she thumbed through the closest book, The Reality Machine.

‘What are you thinking about?’ said Emily.

‘Snails,’ said Jay. ‘When it rains, they’re out there, sucking at the ground. Pour some salt and they foam up at first, and then shrivel and die.’

Such a weird brother. Growing up, he’d seemed in love with life. Only now, he was more obsessed with it, and not with any one thing. As though he was no longer able to compartmentalise his thoughts, or the way they made sense of things. As if every subject, every single theme were boxes marked ‘Jay.’

‘Why are we talking about this?’

‘I’m studying half-life. I told you.’

‘That’s not half-life,’ said Emily, ‘it’s trauma. And that’s different.’

He took a pad from his desk, scrawled snail-shell circles, lines inching in on each other, his left hand grazing the page until he slammed the pen down centre, pushed a dent into the paper.

‘I’m not doing so great.’

She sat, shuffled next to him, and he passed her a pillow for her back.

‘What can I do?’ she said.

‘Stop playing that PJ Harvey album for one thing.’

‘Fat chance. You make boxes?’

‘What do you mean?’ he said.

‘That stuff,’ said Emily. ‘Your fuck-ups, missteps, regrets. You put it in a box.’

‘How big are the boxes? ’Cause I’m going to need a whopper,’ said Jay.

She wanted to tell him that it worried her when he got like this. That she wished he wouldn’t get so sad. But the moment she thought it, she realised she was often sad. That really, all they’d ever agreed upon was that it was never okay for them both to be sad.

‘Hey, Em.’

‘Mm?’

‘If you were struggling, if you ever had a problem, you’d tell me right?’

‘Sure.’

Which was true. If she was struggling now, then she would undoubtedly tell Jay. If she’d not already done something that she knew was wrong, she’d be delighted to begin again, this time with a clean slate.

Hard to tell your brother that you let him down, and harder still to keep it a secret.

Instead, she told him all that she’d learned about half-life at Curtin. How in the BPharm it was more about the half-life of a drug or medicine in the host body.

‘You enjoying the course?’

‘I love it,’ said Emily. ‘Bit lonely, but.’

‘All guys in the course?’

‘Talk shit,’ said Emily.

‘Well, I don’t know,’ said Jay.

‘There are lots of girls,’ she said. ‘It’s not the girls or the boys. It’s just lonely.’

‘It’s often lonely,’ said Jay, and she felt that too, and it wasn’t the city, the weather, or the shape of their world, but a feeling they’d found deep down in the family DNA.

One and Only

Alex’s twenty-first at Slater central, a few months back, was more boozy than beautiful. Local crew and a bunch of gatecrashers. Emily had passed out in the spare room. Woke up to a guy with his tongue in her mouth, his hand down her pants. Told him to stop but he kept going, so she screamed until Alex came in and threw him against the wall.

Jay was in the next room, alphabetising CDs.

Emily was supposed to be grateful for Alex that night, and she had been, for an hour or so. Night wore on, he drank more and more, and became surly, picking fights with any guy who tried it on with Emily. Soon enough, he was just one more drunk, and Jay had pushed him forwards as best as he could through the overcrowded hallway; Alex sticking out his leg, slurring, ‘Try and stop me.’ Jay, with both arms out, pushed hard to move his dipshit boulder of a brother out the door, down the step, and into the waiting cab.

Next day, Jay had said, that was weird, when it wasn’t weird, just another thing that rode shotgun with their brother, and if they asked him what was up, oh the gall, the indignity of even daring to suggest he had a drinking problem.

Then there was Jay, the family work-in-progress, with an undefined, unavoidable oddness, first-year prodigy with a HECS debt and a 486-DX2 PC, 66 megahertz processor with a Sound Blaster audio card, whatever the hell that was.

Her mum hit-and-miss, since, well, the break-up. Better than before, but still not great. Emily thinking maybe she’d turn a corner. But she’s a mum, not a Transperth bus, and so she never made the left, the right, or the shift to second gear. Instead, she’d stalled, middle lane, hazards flashing, with her daughter and two sons in the back; the family coping, surviving like you do, when you’ve broken a window, but you don’t yet have the money to fix it.

Today her mum called Emily from work to say hi. At least, that was the official reason. They talked for a minute, then she skipped to the same track.

‘Do you ever hear from your father?’

‘Let it go, Mum.’

‘You’d tell me, though, if you were in contact, right?’

‘How,’ Emily asked, ‘is this any of your business?’

And yes, she was in contact. And no, it was none of her mum’s business.

Mondays to Fridays, Emily worked one to five. Dependent people of the world queued up at McKenzies Chemist. On days off work, she missed that. She liked the thought of someone needing her.

She dove in headfirst. Reached out a hand to seal the deal, took their change instead of letting it rattle on the counter. Some days, seemed they were drowning. No point giving them a buoy or floaties. Better teaching them to tread water, to kick with their legs, and stay afloat.

They’d come in amped, speaking quickly, clearly when asking for their medication, as though it was a packet of biscuits. But hold up, free and easy, you’re not done yet, not by a long shot: Are you taking other medications? Do you have any allergies? Which brand would you prefer? And why won’t you look me in the eye?

Many sad, some afraid. A smile, some quiet conversation from her side of the counter, as if to say, ‘I see you.’

Who said she didn’t help them by being there? That they needed to go through life alone? It’s important, she thought, to know that somewhere, someone will let you in.

By Friday, it was all she could do not to run to Dom, to cup her hands inside his, ask him, ‘How do you really feel?’ Only in recent times, he was a customer too, so distant and distracted.

And it wasn’t that long ago when they’d snuck into the Inglewood pool, Dom daring her to jump, saying, It’s only scary when you feel the bend of the board. Wasn’t so long ago since he’d promised he would do it if she did it too, and they’d jumped together, sunk down deep, and pulled each other up.

She used to love the water. Could hold her breath for ages, always knowing when she needed to breach and take in air. Survival of sorts. Put Alex in water and he’d try to beat its brains out. Try Jay, same gig, and his wings would soak through, lungs filling up, drowning fast.

She liked the way her father’s letters filled the letterbox. Sometimes Jay said, ‘One for me?’ but it was never going to happen, prodigal son. He hasn’t written to you for a fair while now.

Some nights, used to bug her, what she’d done, but in time got used to being his one and only.

Some nights, drifted up and away from the family tree. Way up high, beyond their reach, and it didn’t matter what they did, if they cared, or whether she’d adhered to their standards and protocol.

Friday nights, so often like weekly wakes. Looking back for fear of looking forwards.

*

Saturday morning, Emily sat hunched at the table still in her pyjamas, half hungover, and nursing a coffee. Jay came in fully dressed, stared at her.

‘What?’ said Emily.

‘Are you trying to be alternative?’ He squinted. ‘What’s that on your hand?’

‘It’s a barcode.’

‘Are you “on special”?’

‘It’s a statement, Jay. About the world.’<

br />

‘It’s a bit sad.’

‘Yes, Jay, that’s what’s sad.’

He dipped a Tim Tam in his coffee, watched it melt, chocolate slick spreading to the edge of the cup. He dropped the Tim Tam onto his plate, licked his fingers clean, and drank the coffee.

‘Where’s Dom?’ said Jay.

‘He had to work.’

Jay smiled. ‘You’re such a great couple.’

‘We’re not a couple. I mean, it’s not like we’re mutually exclusive.’

He took another Tim Tam.

‘Jay.’ He pointed a finger at her, like a game show host. Did that when sprung. Hoped she’d forget or laugh, but she’d been around the block, knew his tricks and tactics. ‘You have your share of the phone bill?’

‘Kind of,’ said Jay.

‘I can’t keep covering you.’

‘Isn’t that what big sisters are for?’

‘No,’ said Emily.

‘You say that,’ said Jay, ‘and yet here we are.’

‘Jay——’

‘It’s cool, I’ll pay you back. Just don’t tell Mum, please?’

He emptied the remaining Tim Tams from the packet onto his plate, put one in his mouth, and left the room.

Jen noticed that her daughter’s room was different. Emily said, ‘I know, Mum. I’m different.’

She had pulled away the wallpaper. Painted the bare walls crimson, strokes occasionally brushing the skirting board until it was simpler to just keep painting. Posters up of PJ Harvey, the Pixies, and a Mutter photomontage: a man on water, suitcase clutched in his left hand, with down–up escalators in the distance.

Things much darker now. PJ staring, naked, her head tilted right, hair in a swirl, perpetually airborne. She understood, she knew what it was like to search for extremes.

She pulled the blinds. Wrote a poem, but the words stuck in her throat. Came out way too slow, an ache in her solar plexus. A weight, a stone, a fear that scared her, made her want to stop.

She scratched the paper, licked the pen marks off her hand.

Lay down. Closed her eyes.

Said, ‘Dom is my boyfriend,’ to test his name on her lips. Felt sad at how it caught, the way her fingers slipped when trying to meld their relationship.

Him standing, foot of her bed. Naked, proud. Like he’d done something other than been given a Y chromosome.

You Belong Here

You Belong Here